This is the place where integrative psychiatry meets practical wellness.

As an integrative psychiatric nurse practitioner, I explore the intersection of conventional mental health care with holistic approaches that honor the whole person. Here you’ll find evidence-based insights on integrative psychiatry topics, alongside practical strategies and actionable advice for improving your mental health and overall well-being.

Whether you’re seeking to understand different treatment modalities, discover new wellness practices, or find tools to support your mental health journey, this space is designed to empower you with knowledge and practical resources for healing and growth.

-

Many people managing anxiety, depression, burnout, or mood fluctuations are interested in natural strategies to complement therapy or medications. In integrative psychiatry, supplements are not a substitute for professional care, but when carefully selected, they can support the brain, nervous system, and overall well-being alongside conventional treatments.

Important: Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before starting any supplement—especially if you take prescription medications, are pregnant, or have other health conditions. Supplements can interact with medications, and quality varies widely. Aim for pharmaceutical-grade brands such as Pure Encapsulations, Thorne, or others recommended by professionals.

1. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

What it is: EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) are essential fatty acids found in fish oil and some algae sources. They are vital for healthy brain function.

Clinical Use: Research supports their role in depression, bipolar disorder, ADHD, cognitive challenges, and inflammatory conditions.

How to use: Look for a ratio of EPA to DHA of roughly 2:1. Depending on the condition, daily doses range from 1–6 grams.

2. Magnesium

What it is: Magnesium is a mineral essential for hundreds of enzymatic reactions, including nerve and muscle function, energy production, and neurotransmitter synthesis. It helps produce “feel-good” neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, and promotes relaxation and sleep.

Clinical Use: Studies suggest magnesium, particularly glycinate or citrate forms, can help reduce mild anxiety and improve sleep. It works by influencing GABA and glutamate signaling, helping the body feel calm.

How to use: Typical doses are 200–400 mg of elemental magnesium at bedtime to support sleep. For anxiety or focus, smaller doses can be spread throughout the day. Avoid magnesium oxide, which is less absorbable and more likely to cause digestive upset.

3. Inositol

What it is: Inositol is a sugar alcohol involved in cellular signaling. Though not technically a B vitamin, it’s often grouped with the B-complex family.

Clinical Use: Evidence supports its use in anxiety disorders, OCD, insomnia, bipolar depression, and PMDD.

How to use: Doses vary depending on the condition, often split into multiple servings per day, with total daily amounts up to 18 grams. For insomnia, a single 6-gram dose at bedtime is typical.

4. L-Theanine

What it is: L-theanine is an amino acid naturally found in green tea leaves.

Clinical Use: Helpful for anxiety, situational stress, and ADHD.

How to use: Can be taken alone or combined with small amounts of caffeine to improve focus without jitteriness. Typical adult doses are up to 1 gram per day, divided throughout the day depending on need. Lower doses are recommended for children. It is generally considered safe in pregnancy and is often included in sleep-support combinations.

5. SAMe (S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine)

What it is: SAMe is a naturally occurring compound involved in methylation, neurotransmitter synthesis, and energy metabolism. It plays a key role in the production of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.

Clinical Use: Research shows SAMe can support mood in depression.

How to use: Start with a low dose and gradually increase under medical supervision, as it can be activating. Usually taken twice daily, with the second dose before noon to prevent insomnia. Typical safe doses range from 400–1,600 mg per day.

Choosing High-Quality Supplements

- Pharmaceutical-grade brands are recommended for purity and consistency. Examples include Pure Encapsulations, Thorne, Douglas Labs, Designs for Health, Metagenics, Orthomolecular Products, Integrative Therapeutics, Klaire Labs, among others.

- Professional guidance matters: In integrative psychiatry, supplements are selected based on individual biochemistry, medications, and therapeutic goals.

Complementary Lifestyle Strategies

Supplements work best when combined with a holistic approach:

- Follow a nutrient-rich diet, such as a plant-forward or Mediterranean-style diet, while limiting processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates.

- Support your body with adequate protein, Omega-3s, B vitamins, Vitamin C, magnesium, and zinc.

- Include daily movement or exercise.

- Maintain sleep hygiene and establish a relaxing bedtime routine.

- Incorporate stress-reduction practices, like yoga, mindfulness, or breathwork. Consistency is key.

- Surround yourself with supportive relationships and engage in psychotherapy for coping strategies and resilience building.

This whole-person approach exemplifies integrative psychiatry: combining evidence-based conventional and natural tools to support long-term mental wellness.

Bottom Line

Omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, inositol, L-theanine, and SAMe are among the many researched supplements for anxiety and depression. When used under professional guidance, they can enhance therapy, medications, and lifestyle interventions—supporting the brain, body, and nervous system for sustained mental health.

-

In integrative psychiatry, we often focus on a patient’s gut health. Scientifically, this connection is called the gut–brain axis, which is the constant two-way communication between your gut and your brain. Research on the microbiome shows that the bacteria living in your intestines influence mood, stress, and mental performance. Michael Gershon’s groundbreaking book The Second Brain revealed the importance of the nervous system of the gut, also called the enteric nervous system, a vast network of neurons in the gut that interacts with the brain and immune system. Understanding the gut–brain axis is transforming how integrative psychiatry approaches anxiety, depression, mood disorders, and stress resilience.

The Enteric Nervous System: The “Second Brain”

The enteric nervous system contains more neurons than the spinal cord and can mediate reflexes without the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS). It also produces neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, glutamate, noradrenalin, and GABA (gaba-aminobutyric acid). For example, over 95% of the body’s serotonin and 50% of the body’s dopamine originates in the gut (Hamamah, et al., 2022). This is why as many as 40% of patients who see a gastroenterologist present with symptoms that have no clear anatomical or chemical cause, a set of conditions known as Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBIs). In integrative psychiatry, this matters because changes in the gut–brain axis—from poor diet, chronic stress, or antibiotics—can alter neurotransmitter signaling and, therefore, mood, resulting in a variety of disorders such as depression, anxiety, autism, and ADHD. Gershon called the gut our “second brain” for good reason: it not only regulates digestion but also controls our mood by connecting the CNS with the microbiome.

How the Microbiome Talks to the Brain

Your microbiome—the trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses in your intestines—affects the gut–brain axis through:

- Neural pathways: The vagus nerve is the main mediator for communication between the gut and the brain (Cryan and Dinan, 2012).

- Immune signaling (cytokines and inflammation): Microorganisms in the gut affect the immune system, which in turn activates its cells to release inflammatory cytokines. It’s important to know that cytokines can cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), thus affecting the brain and altering mood (Foster and Neufeld, 2013).

- Hormonal pathways (stress hormones, gut peptides): There is an intimate connection between the gut–brain axis and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is the regulatory center of the physiological stress response (Grenham, S., et al., 2011).

- Microbial metabolites (short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan derivatives): Bacteria in our gut synthesize important chemicals, such as the short-chain fatty acid butyrate (which affects neurotransmitters and, therefore, mood) and tryptophan (an amino acid that is a precursor to serotonin) (O’Mahony et al., 2014).

- Animal and human studies show that a disrupted microbiome (dysbiosis) is linked to depression, anxiety, and cognitive changes. In integrative psychiatry, clinicians see the gut–brain axis as a modifiable factor—an area where lifestyle, nutrition, and targeted supplements can complement medication and therapy (Butler et al., 2019).

Stress, the Microbiome, and Mental Health

Chronic stress changes the microbiome and weakens the gut barrier, fueling inflammation that feeds back to the brain. In humans, early life stress, poor diet, or repeated antibiotics can disrupt the gut–brain axis and increase vulnerability to anxiety or depression (Foster and Neufeld, 2013). This is why integrative psychiatry emphasizes stress management, nutrition, and sleep alongside standard treatments.

Diet and Lifestyle: Building a Healthier Gut–Brain Axis

Key habits to support the microbiome and the gut–brain axis:

- Fiber-rich, plant-based foods act as prebiotics, feeding beneficial bacteria and producing anti-inflammatory metabolites. Examples include bananas, raw garlic, raw onion, raw leeks, asparagus, apples, oats, barley, and flaxseeds (Holscher, 2017).

- Fermented food acts as a source of probiotics, introducing live microbes. Examples include kimchi, sauerkraut, yogurt, kefir, miso, tempeh, kombucha, fermented cheese (Gouda, cheddar, Swiss), and sourdough bread (Marco et al., 2021).

- Healthy fats and balanced protein support cell membranes and reduce inflammation (Costantini, et al., 2017).

- Stress management—including breathwork, yoga, and meditation—stabilizes both the enteric nervous system and the microbiome.

- Sleep and exercise regulate hormones and microbial diversity (Madison & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2019).

In integrative psychiatry, these strategies are core—not just add-ons.

Probiotics, Testing, and Integrative Psychiatry

Sometimes, diet and lifestyle changes aren’t enough. Certain probiotics—sometimes called psychobiotics—show promise for improving mood or stress resilience (Dinan & Cryan, 2017). In integrative psychiatry, stool or microbiome testing may be considered when symptoms persist, but these tests are used as tools rather than stand-alone answers. Lab work to check for inflammation, nutrient status, or hormones can also guide interventions aimed at the gut–brain axis.

The Bottom Line

Your gut is not just a digestive organ; it’s a key player in mental health. The microbiome, the enteric nervous system, and the gut–brain axis form an interconnected system that shapes mood, cognition, and stress response. Integrative psychiatry uses this science to move beyond symptom management and create whole-person care plans—combining medication, therapy, nutrition, stress reduction, and targeted supplements to support both the gut and the brain.

References

Butler, M. I., Morkl, S., Sandhu, K. V., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2019). The gut microbiome and mental health: What should we tell our patients? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 64(11): 747-760. doi: 10.1177/0706743719874168

Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nature Reviews. 13(10): 701-712. DOI: 10.1038/nrn3346

Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). The microbiome-gut-brain axis in health and disease. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 46(1):77-89. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2016.09.007

Fikree, A., Byrne, P. (2021). Management of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Med (Lond). 21(1): 44-52. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0980

Foster, J. A., & McVey Neufeld, L. (2013). Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends in Neurosciences, 36(5): 305-312. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005

Foster, J.A., Rinaman, L., & Cryan, J.F. (2017). Stress and the gut–brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 7, 124–136.

Gershon, M.D. (1998). The Second Brain: A Groundbreaking New Understanding of Nervous Disorders of the Stomach and Intestine. HarperCollins.

Grenham, S., Clarke, G., Cryan, J. F., Dinan, T. G. (2011). Brain-gut-microbiome communication in health and disease. Frontiers in Physiology. 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2011.00094

Hamamah, S., Aghazarian, A., Nazaryan, A., Hajnal, A., Covasa, M. (2022). Role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in regulating dopaminergic signaling. Biomedicines, 10(2): 436. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020436

Holscher, H. D. (2017). Dietarty fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 8(2):172-184. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756

Loh, J.S., Mak, W.Q., Tan, L.K.S., et al. (2024). Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(37). DOI: 10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1

Madison, A., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2019). Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human-bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 28:105-110. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.01.011

Marco, M. L., Sanders, M. E., Ganzle, M., Arrieta, M. C., Cotter, P. D., De Vuyst, L., Hill, C., Holzapfel, W., Lebeer, S., Merenstein, D., Reid, G., Wolfe, B. E., & Hutkins, R. (2021). The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on fermented foods. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 18(3): 196-208. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00390-5

O’Mahony, S. M., Clarke, G., Borre, Y. E., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2014). Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behavioral Brain Research. 277:32-48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027

-

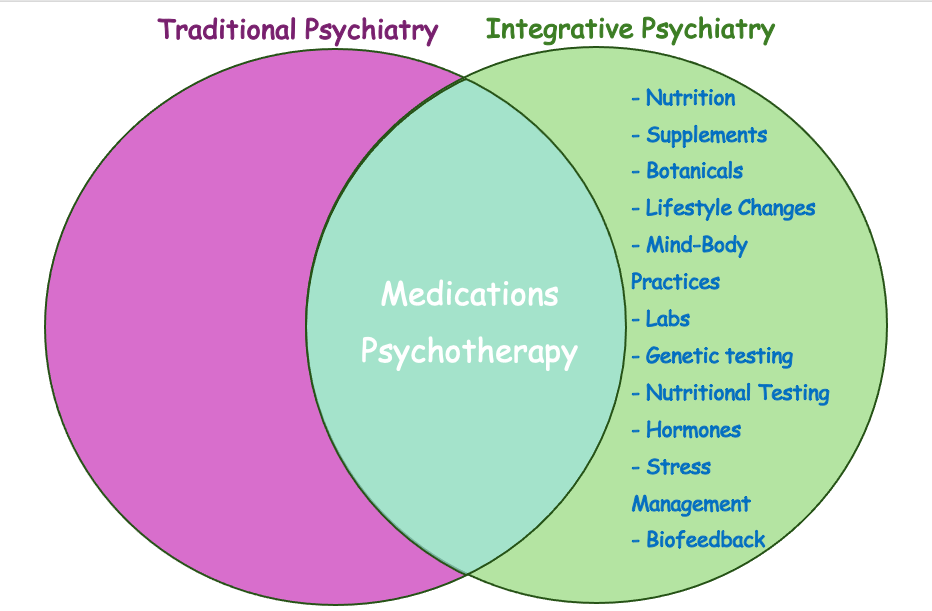

When most people think of psychiatry, they picture a quick check-in with a prescribing doctor—answering yes-or-no questions and leaving the office within 15–20 minutes. From my experience as a provider who once worked in this fast-paced model, many clients feel rushed and only superficially helped. While this conventional model of psychiatry has helped countless people, it is not sufficient for everyone. For a large subgroup of individuals, mental health needs to be addressed in a fundamentally different way. What I see every day is a growing need for care that treats the whole person—mind, body, and lifestyle—not just the diagnosis. Many of my patients do not get better with medications alone. This is exactly where integrative psychiatry comes in.

What Is Conventional Psychiatry?

Conventional (or “traditional”) psychiatry focuses on diagnosing mental health conditions and treating them primarily with medications and psychotherapy. Most appointments are 15–20 minutes long—barely enough for medication management, let alone meaningful psychotherapy. In traditional psychiatry, we typically see:

- Assessment: Symptom checklists, brief histories, and standardized diagnostic criteria such as the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) that psychiatrists use to match symptoms with a diagnosis

- Treatment tools: Psychiatric medications, referrals for therapy, and sometimes hospitalization.

- Strengths: Decades of research on medications, clear evidence-based protocols, and effective interventions for acute states.

This approach can absolutely be lifesaving—I’ve seen it work wonders both inpatient and outpatient. But for many people—especially those with chronic stress, mild to moderate symptoms, or complex conditions—the conventional model feels limited and impersonal. It doesn’t look deeply enough at all aspects of the problem.

What Is Integrative Psychiatry?

Integrative psychiatry blends the best of conventional psychiatry with evidence-based complementary and lifestyle approaches. It’s a “whole-person” framework that looks beyond symptom relief to the root contributors to mental health. Patients receive not just a diagnosis and a prescription but also a roadmap for long-term resilience and well-being.

Key features of integrative psychiatry include:

- Comprehensive evaluation: In addition to a psychiatric interview, your clinician may look at nutrition, sleep, movement, stress levels, trauma history, social support, hormone status, lab results, and even genetic and nutritional testing.

- Expanded toolkit: Medications when needed plus targeted supplements, nutritional strategies, movement, stress-reduction practices, psychotherapy, and mind–body therapies such as breathwork or biofeedback.

- Collaborative care: In my integrative psychiatry practice, I provide clear explanations of each treatment option—its benefits, limitations, and potential side effects—so patients understand the reasoning behind recommendations. This education allows them to take part in mutual decision-making, rather than feeling left out of their own care.

Why Integrative Psychiatry Is Different

Integrative psychiatry recognizes that mental health is inseparable from physical health, relationships, and environment. It goes beyond symptom management to address nutrition, sleep, hormones, inflammation, stress, and meaning. By weaving together medication management with mind–body practices, nutritional guidance, and psychotherapy, integrative psychiatry creates a far more personalized and empowering path to wellness.

Many people come to integrative psychiatry after feeling unheard or stuck in the conventional model. Others start here from the beginning because they want prevention, resilience, and a values-aligned approach. Whatever the reason, the goal of integrative psychiatry is the same: to treat the whole person, not just the diagnosis.

The Bottom Line

Conventional psychiatry saves lives, especially in crises. But for those whose needs extend beyond a prescription, integrative psychiatry offers a comprehensive, evidence-based, and collaborative way to heal. By bringing together the science of modern psychiatry with nutrition, lifestyle, and mind–body practices, integrative psychiatry empowers patients to recover, grow, and thrive.

The Main Differences at a Glance

Aspect Conventional Psychiatry Integrative Psychiatry Focus Symptom management Root causes + symptom relief Tools Medications, psychotherapy Medications, psychotherapy, lifestyle, nutrition, supplements, mind–body practices Evaluation Standard psychiatric assessment Expanded assessment (labs, genetic testing, diet & nutritional testing, sleep, hormones, inflammation) Patient Role Passive, compliance-oriented Active, collaborative